What an IVF Story Taught Me About Translation

In a cutting-edge IVF clinic, a new genomic test promises to improve the success rate of in vitro fertilization. The science behind it is growing, and hopeful parents-to-be are eager to try it. Yet as this innovation makes its way from lab to clinic, something strange happens. Two leading professional bodies step in to issue guidelines – and they completely contradict each other. Both groups have access to the same data, but each tells a different story about what doctors should do. Confused? So were the clinicians on the ground. How can one discovery split into two narratives?

Two Groups, One Science, Different Worlds

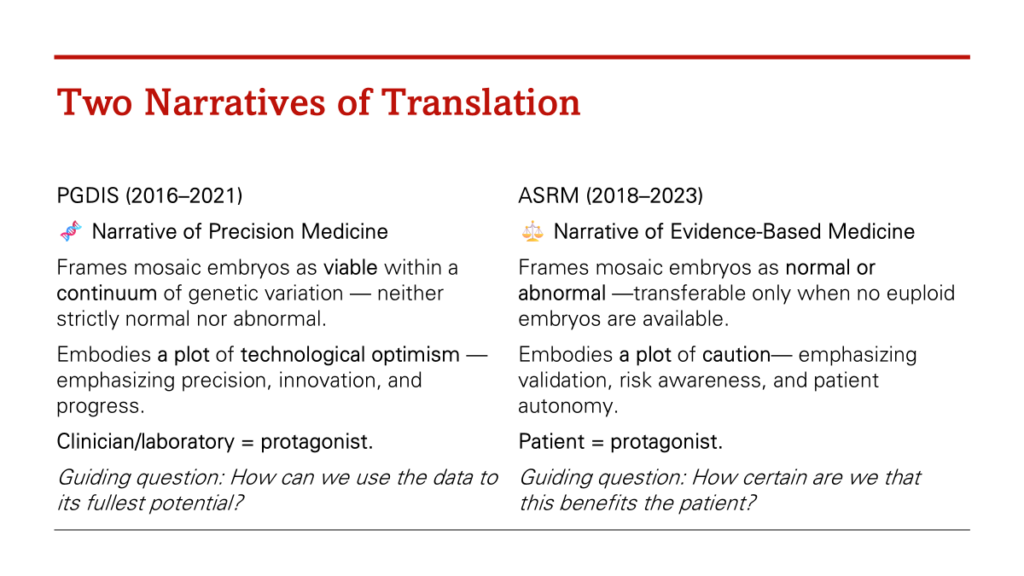

In the IVF story above, the Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis International Society (PGDIS) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) held different institutional values and professional identities. Those deeper commitments led them to translate the evidence in diverging ways – and to tell different stories about the same science.

Both professional bodies had access to the same clinical studies. But each group brought its own cultural lens: one narrative stressed the promise of innovation (embracing the new genomic test as a hopeful leap forward), while the other sounded a note of caution (worrying about ethics and uncertainties). Neither was “wrong” in a straightforward sense – each was translating the evidence to fit what they believed was right for patients and society. In other words, they weren’t just exchanging facts; they were negotiating meaning.

We often talk about “following the science.” But anyone who has worked in healthcare—or lived through a disease—knows that science never travels alone. It moves with stories, assumptions, values, and cultural baggage. It has to be read, interpreted, and translated every time it enters a new room.

“It has to be read, interpreted, and translated every time it enters a new room.”

This point became crystal clear when my co-author, Mona Baker, and I began examining how new genomic technologies are being introduced into IVF practice as part of our forthcoming book, Beyond the Bedside: Reimagining Narrative Medicine for Knowledge Translation in Reproductive Health (Cambridge University Press). What we found was not a simple story of evidence guiding policy, but a full-blown drama of interpretation—one that reveals why medicine urgently needs a translational medical humanities approach.

The Hidden Work of Translation

What this IVF example shows is that evidence doesn’t simply “flow” from lab bench to clinic. It must be translated—and translation isn’t neutral.

PGDIS and ASRM each bring their own histories, identities, professional cultures, and moral landscapes. They inhabit different “epistemic worlds”:

- One places innovation and global scientific leadership at the center.

- The other foregrounds professional responsibility, public accountability, and ethical risk.

Same data, different stories.

This is not a failure of science. It’s simply how meaning works.

As in any translation—between languages, cultures, or scientific systems—something shifts. Words like risk, normality, benefit, and uncertainty don’t carry fixed meanings. They get re-shaped as soon as they enter new institutional or cultural settings.

The humanities have spent centuries thinking about this kind of meaning-making. Medicine, not so much.

Why This Matters Beyond IVF

We tend to talk about knowledge translation as if it’s a technical pipeline: gather the evidence, synthesize the evidence, implement the evidence. Problem solved.

But the IVF case exposes the enormous interpretive space between those steps—the space where:

- values come into play,

- professional identities matter,

- metaphors do hidden work,

- and uncertainty refuses to be tamed.

This interpretive space is where decisions are actually made.

And if we ignore it—if we treat translation as mere logistics—we shouldn’t be surprised when guidelines conflict, uptake falters, or public trust erodes.

Translational Medical Humanities: A Different Way of Seeing

This is where a translational medical humanities approach becomes essential.

Instead of treating the humanities as an add-on for empathy training or ethics modules, translational medical humanities recognize the humanities as core partners in understanding how medical knowledge moves and morphs.

From this viewpoint:

- Every guideline is a story about evidence.

- Every systematic review is a genre that organizes meaning.

- Every public health message is a translation between worlds.

- Every clinical encounter is a negotiation between epistemic cultures.

The humanities give us tools to analyze these stories, genres, and negotiations—not to weaken science, but to strengthen its real-world impact.

Because if we want evidence to matter, we need to understand how it becomes meaningful.

Rethinking Translation as Encounter

The IVF example shows that translation isn’t a one-way path from experts to users. It’s a meeting place, a crossroads where science interacts with:

- institutional priorities,

- moral judgments,

- cultural assumptions,

- and patient stories.

Instead of managing translation as a tidy chain of steps, translational medical humanities invites us to inhabit translation: to pay attention to how evidence is narrated, interpreted, contested, and transformed.

This isn’t a distraction from science. It’s the condition for science to work.

So What Do We Do With This?

If we take the IVF case seriously—and we should—it suggests a few shifts in how we approach medical knowledge more generally:

- Make the interpretive work visible.

Instead of pretending guidelines are neutral products, show how they’re shaped by values and narratives. - Invite humanities scholars into the room earlier.

Not to moralize or critique from the sidelines, but to help analyze meaning-making as part of translational science. - Create spaces for negotiation.

Bring patients, clinicians, policymakers, and researchers together to discuss how evidence translates into practice. - Embrace uncertainty honestly.

Uncertainty isn’t a flaw. It’s part of what makes translation necessary in the first place.

Medicine Needs the Humanities More Than Ever

The IVF story is just one example, but it illustrates something much bigger:

Medical knowledge does not travel on its own. We carry it. We interpret it. We translate it.

If we want better health policies, better guidelines, and better patient care, we need to understand these translations—not as afterthoughts, but as central components of medical practice.

“Medical knowledge does not travel on its own. We carry it. We interpret it. We translate it.”

Translational medical humanities isn’t about making medicine more “humanistic” in a soft, aesthetic way. It’s about making medicine more accurate about how knowledge actually works in the real world.

And if we can get that right, the gap between knowledge and action starts to close—not through better pipelines, but through better stories, better conversations, and better translations.

Leave a Reply